A Comprehensive Biography of Howlin’ Wolf

Introduction

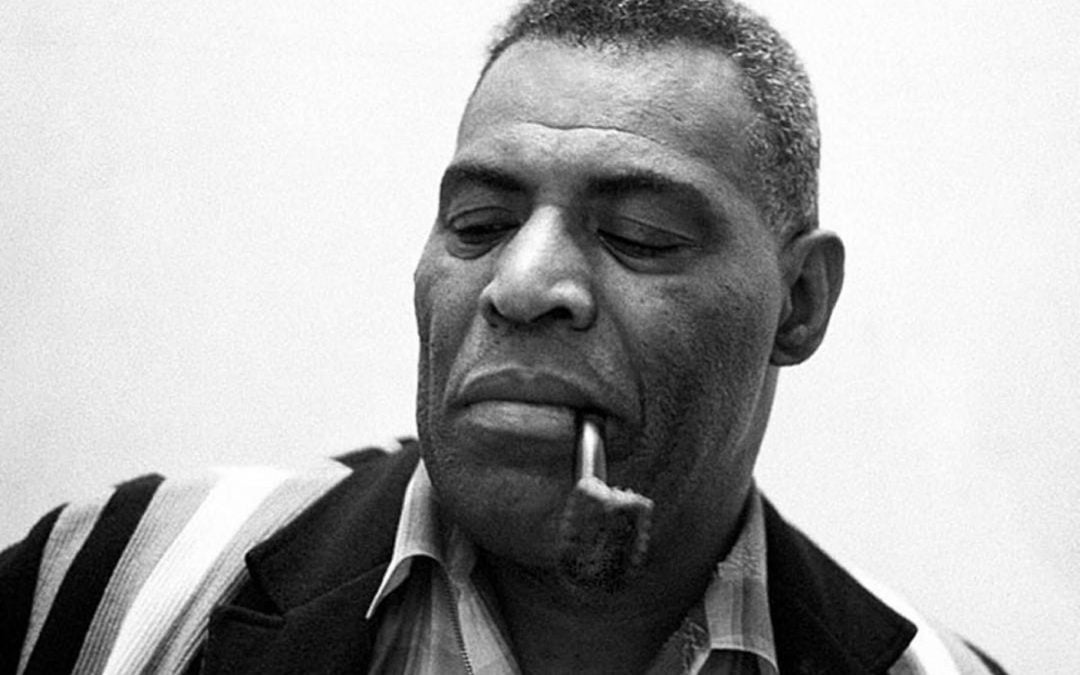

Chester Arthur Burnett (June 10, 1910 – January 10, 1976), universally known by his stage name Howlin’ Wolf, was an American blues singer, guitarist, and harmonica player whose imposing presence and raw, powerful voice left an indelible mark on the landscape of American music. A towering figure both literally and figuratively, standing over six feet three inches tall and weighing nearly 300 pounds, Howlin’ Wolf was a primal force in the blues, capable of rocking a venue to its foundations while simultaneously captivating and even startling his audience. His distinctive, raspy growl and signature falsetto moans, influenced by the yodels of Jimmie Rodgers, set him apart as one of the most influential blues musicians of all time.

Howlin’ Wolf was at the forefront of transforming the acoustic Delta blues of the rural South into the electrified, urban Chicago blues that would become a cornerstone of rock and roll. Over a career spanning four decades, he recorded a diverse range of genres, including blues, rhythm and blues, rock and roll, and even psychedelic rock. His profound impact on music is evident in the countless artists he influenced, from the Rolling Stones and Jimi Hendrix to Led Zeppelin and The Doors, many of whom covered his classic songs, bringing his music to new, wider audiences.

This biography will delve into the life of Howlin’ Wolf, exploring his challenging childhood, his formative years in the Mississippi Delta, his rise to prominence in West Memphis and Chicago, his major musical contributions, and his enduring legacy. Through an examination of his personal journey and artistic evolution, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of the man behind the legendary howl.

Childhood

Chester Arthur Burnett was born on June 10, 1910, in White Station, Mississippi, a small town near West Point. His early life was marked by poverty and hardship, a common experience for many African Americans in the Deep South during that era. His parents, Leon “Dock” Burnett, a sharecropper, and Gertrude Jones, separated when he was just one year old. Following the separation, young Chester and his mother moved to Monroe County, Mississippi, where Gertrude became known as an eccentric religious singer, performing and selling her self-penned spirituals on the streets.

Burnett’s childhood was far from idyllic. He acquired his famous nickname, “Wolf,” from his grandfather, who would playfully scare the youngster with tales of a wolf in the woods that would come for him if he misbehaved. This playful teasing led the rest of the family to call him “Wolf” and even howl at him. However, the harsh realities of his upbringing soon overshadowed such lighthearted moments. His mother, who reportedly disapproved of his singing what she called “the devil’s music,” sent him away to live with an uncle. This period was particularly difficult, as his uncle treated him with extreme cruelty, often whipping him with a bullwhip and forcing him to eat separately from the rest of the family.

At the tender age of thirteen, unable to endure the abuse any longer, Chester ran away from his uncle’s home. He made his way to the Mississippi Delta, a region that would profoundly shape his musical destiny. There, he eventually reunited with his father and his father’s new family on a plantation near Ruleville, Mississippi, where he began working as a sharecropper. This return to his father’s side, though still involving hard labor, offered a semblance of stability compared to the torment he had endured, setting the stage for his eventual immersion in the blues culture of the Delta.

Youth

The Mississippi Delta proved to be a fertile ground for Chester Burnett’s burgeoning musical aspirations. It was here that he encountered Charley Patton, a legendary Delta blues musician whose rough voice and hard-living champion status made him an inspiring role model. Patton, recognizing a spark in the young Burnett, taught him a few chords on the guitar, laying the foundation for his future career. In January 1928, Burnett’s father purchased him a guitar, and he began to play regularly, often teaming with Patton, who further honed his showmanship skills.

Burnett quickly realized that the life of a blues musician was far more appealing than the arduous existence of a sharecropper. He began to wander the Delta regions of Mississippi and Arkansas, performing his music wherever he could earn a living. His imposing physical stature—over six feet three inches tall and weighing around 275 pounds—combined with his powerful, howling voice, made him a well-known figure in the region. He was one of the first blues musicians many audiences had ever seen playing an electric guitar, which, coupled with his percussive harmonica playing and emotive singing, growling, and howling, solidified his stage persona and earned him the enduring nickname “Howlin’ Wolf”.

His musical education continued as he learned to play the harmonica from Aleck “Rice” Miller, also known as Sonny Boy Williamson, who was married to Burnett’s half-sister Mary. This addition to his repertoire further enriched his sound. Throughout the 1930s, Howlin’ Wolf performed alongside other blues luminaries such as Robert Johnson, Son House, Johnny Shines, Willie Brown, and Robert Jr. Lockwood, absorbing their styles and contributing to the vibrant blues scene of the era. Despite his growing commitment to music, he maintained a connection to his roots, faithfully returning each spring to plow his father’s land, even after his family moved to a large Arkansas plantation in Wilson (Mississippi County) in 1933, and later to the Nat Phillips Plantation on the St. Francis River in 1934. This period of wandering and learning in the Delta forged the raw, untamed sound that would define Howlin’ Wolf’s legendary career.

Adulthood

Howlin’ Wolf’s journey into adulthood was marked by a brief and ill-suited stint in the U.S. Army, from which he was discharged after suffering a nervous breakdown. Following his military service, he returned to farming, first on the Phillips Plantation and then for two years in Penton, Mississippi, where he balanced his agricultural work by night with his passion for music. In Penton, he met Katie Mae Johnson, whom he married on May 3, 1947, though their marriage would later end.

In 1948, a pivotal move brought Howlin’ Wolf to West Memphis, Arkansas, a town bustling with blues clubs and at the forefront of the newly amplified blues music scene. While he initially took a factory job, the allure of the local blues clubs was undeniable. He quickly adapted to the electric sound, forming his own band, The House Rockers, and committing himself fully to a career in music. It was during this period that he began performing on local radio station KWEM in West Memphis, where he not only produced his own program but also sold advertising for it.

His radio presence caught the attention of Sam Phillips, the legendary Memphis recording studio owner who would later found Sun Records. Phillips, deeply impressed by Wolf’s raw talent, recorded him and subsequently leased the recordings, including

“Moanin’ At Midnight” and “How Many More Years,” to Chess Records in Chicago. These tracks became a double-sided hit on Billboard magazine’s R&B top ten, marking Howlin’ Wolf’s breakthrough into the national music scene.

In September 1951, Howlin’ Wolf officially signed with Chess Records, and the Chess brothers convinced him to relocate to Chicago in the winter of 1952. Upon his arrival, he quickly established himself in the vibrant Chicago blues scene, assembling a new band that included the young and explosive guitarist Hubert Sumlin, who would remain his longest-running musical associate. Sumlin’s angular and aggressive guitar style perfectly complemented Wolf’s powerful vocals, creating a distinctive sound that would define Chicago blues.

His collaboration with Chess Records’ staff writer Willie Dixon proved particularly fruitful, leading to a string of blues classics that would become standards, including “Evil” (1954), “Smokestack Lightnin'” (1956), “Spoonful,” “Wang Dang Doodle,” “Back Door Man,” and “Red Rooster”. “Smokestack Lightnin'” notably peaked at number eleven on both the Cash Box Hot Chart and Billboard’s R&B chart.

Howlin’ Wolf’s popularity grew steadily throughout the 1950s and 1960s. He toured widely, playing prestigious venues like New York’s Apollo Theater in 1955, and was recognized among the top R&B vocalists by Cash Box magazine. While his records didn’t always top the national charts, they sold consistently well, especially in the South, where his influence often surpassed that of his contemporary, Muddy Waters.

On March 14, 1964, Howlin’ Wolf married Lillie Handley Jones, a property owner and astute money manager who provided stability and remained with him until his death. The mid-1960s saw his music gain international recognition, particularly in Europe, where he toured as part of the American Folk Blues Festival. His appearance on the ABC TV show Shindig in 1965 with the Rolling Stones, who idolized him and had a number-one hit with their cover of his song “The Red Rooster,” further cemented his status as a blues icon. He continued to perform at major festivals like Newport, Berkeley, and Ann Arbor, releasing albums such as Real Folk Blues (1966) and More Real Folk Blues (1967).

Despite deteriorating health, including a heart attack in 1969 and ongoing kidney problems, Howlin’ Wolf continued to tour and record. In 1970, he recorded The London Howlin’ Wolf Sessions with British rock stars like Eric Clapton, Mick Jagger, and Ringo Starr, which became his only album to appear on the Billboard 200. Though his later album Message to the Young (1971) was considered a misstep, he continued to perform, even against doctor’s orders, demonstrating his unwavering dedication to the blues.

Major Compositions

Howlin’ Wolf’s discography is a testament to his profound influence on the blues and rock music. His early recordings, particularly those produced by Sam Phillips in Memphis, laid the groundwork for his distinctive sound. The double-sided hit “Moanin’ At Midnight” and “How Many More Years” (1951) served as his powerful introduction to a wider audience, showcasing his raw vocal power and innovative approach to the blues.

Upon his move to Chess Records in Chicago, Howlin’ Wolf’s output became even more prolific and influential, largely due to his collaboration with bassist and songwriter Willie Dixon. Dixon penned many of Wolf’s most enduring classics, contributing significantly to the Chicago blues sound. Among these iconic compositions are:

•”Evil” (1954): This track became one of Wolf’s biggest hits at the time, landing on the Cash Box magazine Hot Chart and demonstrating his growing commercial appeal.

•”Smokestack Lightnin'” (1956): Considered by many to be his masterpiece, this song peaked at number eleven on both the Cash Box Hot Chart and Billboard’s R&B chart. Its haunting melody and evocative lyrics made it a blues standard, later finding significant success in the UK charts in 1964.

•”Spoonful” (1960): A powerful and enduring blues anthem, “Spoonful” became a staple in his live performances and was widely covered by rock bands, including Cream.

•”Wang Dang Doodle” (1961): Another Willie Dixon composition, this lively and infectious track showcased Wolf’s versatility and ability to deliver upbeat, danceable blues.

•”Back Door Man” (1961): This song, with its suggestive lyrics and driving rhythm, became another signature tune for Wolf and was famously covered by The Doors.

•”The Red Rooster” (1961): Also known as “Little Red Rooster,” this track gained immense popularity when covered by the Rolling Stones, becoming a number-one hit in England and introducing Wolf’s music to a new generation of rock fans.

•”I Ain’t Superstitious” (1961): This track, with its memorable guitar riff and Wolf’s commanding vocals, also became a blues standard and was covered by artists like Jeff Beck.

•”Killing Floor” (1964): A later classic, this song featured a modern backbeat and a catchy guitar riff from Hubert Sumlin, so compelling that Led Zeppelin famously appropriated it for one of their early albums.

Howlin’ Wolf’s studio albums also played a crucial role in cementing his legacy. His first album on Chess, Moaning in the Moonlight (1959), compiled many of his early singles and showcased his raw power. This was followed by the self-titled Howlin’ Wolf (1962), often referred to as the “Rocking Chair” album due to its iconic cover art. Greil Marcus of Rolling Stone magazine lauded it as “the finest of all Chicago blues albums”.

Later in his career, despite declining health, Wolf continued to record. The London Howlin’ Wolf Sessions (1971), recorded with an all-star lineup of British rock musicians including Eric Clapton, Mick Jagger, and Ringo Starr, was a significant commercial success, becoming his only album to chart on the Billboard 200. While some later experimental efforts, such as Message to the Young (1971), were less critically acclaimed, his body of work remains a cornerstone of the blues genre, influencing countless musicians across various genres for decades to come.

Death

By the early 1970s, Howlin’ Wolf’s health had significantly deteriorated, a consequence of years of relentless touring, a demanding lifestyle, and chronic health issues. He had endured numerous heart attacks and suffered from kidney damage, reportedly exacerbated by an automobile accident that sent him through the car’s windshield. Despite his failing health, Wolf’s dedication to his music remained unwavering. He continued to perform, often against the advice of his doctors, who had ordered him to stop after his kidneys began failing and he started hemodialysis treatments in May 1971. His bandleader, Eddie Shaw, would often ration Wolf to a mere half-dozen songs per set to conserve his strength. Yet, even in his weakened state, the old fire would occasionally blaze forth, reminding audiences of the immense power he once commanded. His final live and studio recordings from this period still showcased his ability to captivate and move an audience.

Howlin’ Wolf’s last public performance took place in November 1975, where he shared the stage with fellow blues legend B.B. King. It was a poignant farewell from a man who had given his life to the blues. Just two months later, on January 7, 1976, he was diagnosed with a brain tumor. He underwent surgery, but tragically, he never recovered from the procedure. Chester Arthur Burnett, the mighty Howlin’ Wolf, was removed from life support and passed away on January 10, 1976, at the Hines V.A. Hospital in Hines, Illinois.

Conclusion

Howlin’ Wolf’s passing marked the end of an era, but his legacy as one of the most influential figures in blues and rock music continues to resonate. His fearsome physical presence, roaring howl, and profound musicality carved an indelible niche in American musical history. He was a pioneer, transforming the raw, acoustic sounds of the Delta into the electrified, urban blues that would define Chicago and inspire generations of musicians across genres.

His impact was immediately recognized and continues to be celebrated. A life-size statue was erected in a Chicago park shortly after his death, a permanent tribute to his larger-than-life persona. His bandleader, Eddie Shaw, kept his memory and music alive by continuing to perform with The Wolf Gang for several years. A child-education center in Chicago was named in his honor, further cementing his place in the community.

Howlin’ Wolf received numerous posthumous accolades, solidifying his status as a musical titan. He was inducted into the Blues Foundation Hall of Fame in 1980 and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1991. A few years later, his image graced a United States postage stamp, a testament to his enduring cultural significance. His biography, Moanin’ at Midnight by James Segrest and Mark Hoffman, published in 2004, further chronicles his remarkable life and career.

Today, Howlin’ Wolf’s legacy is celebrated annually at the Howlin’ Wolf Memorial Blues Festival in West Point, Mississippi, and through the Howlin’ Wolf Museum, ensuring that his contributions to music are never forgotten. His songs remain staples in the repertoires of countless artists, and his distinctive voice and style continue to inspire new generations of musicians. Howlin’ Wolf is not merely a figure from the past; he is a permanent, howling force in the ongoing narrative of American music, a testament to the power of raw talent, unwavering dedication, and the enduring spirit of the blues.

Comments are closed