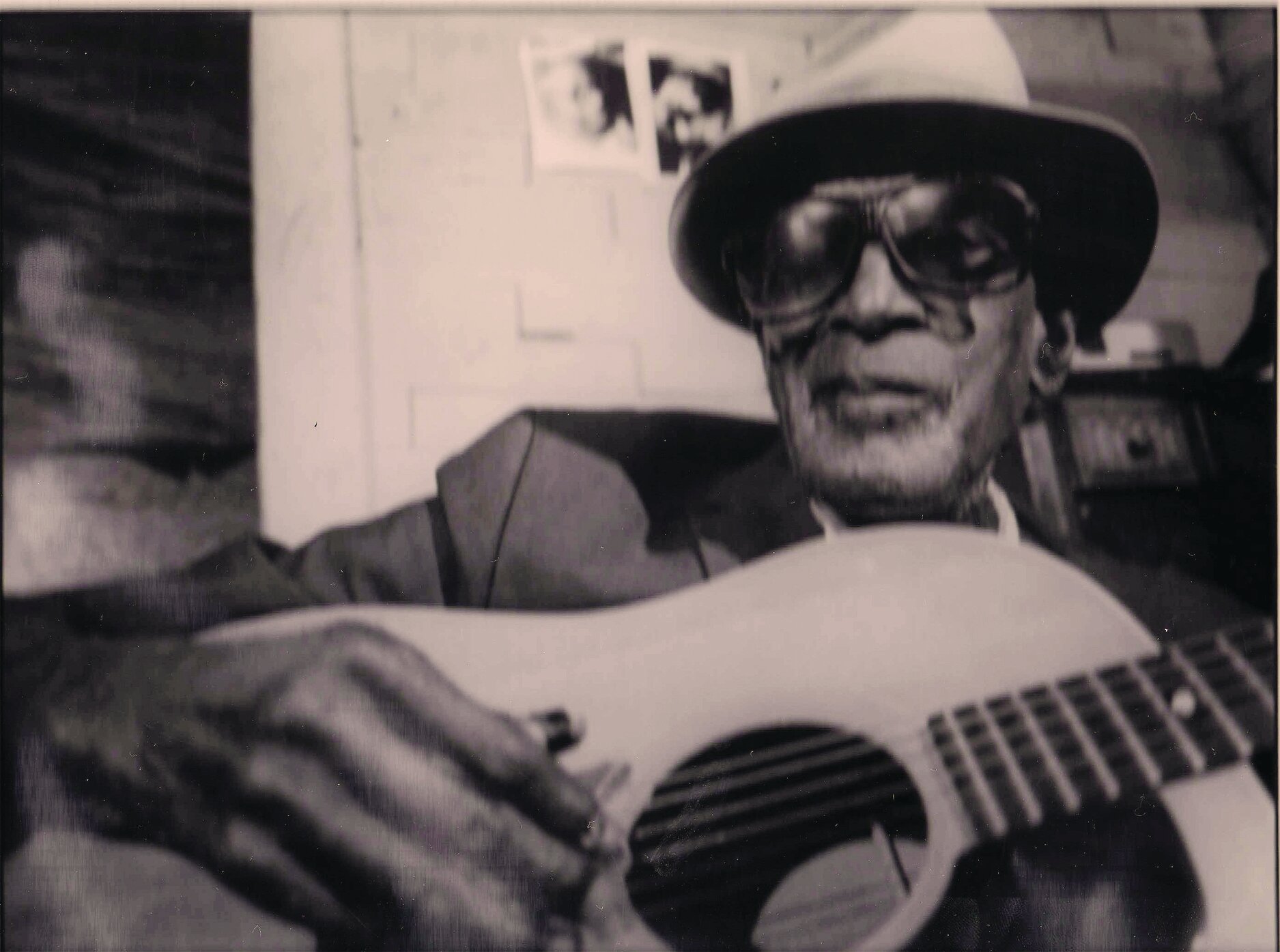

Sleepy John Estes – A Complete Biography

Introduction

Sleepy John Estes (John Adam Estes) was one of country blues’ most expressive singer-songwriters, famed for a high, pleading vocal delivery and story-songs drawn from everyday life in Brownsville, Tennessee. His work bridged the pre-war Memphis jug-band scene and the 1960s folk-blues revival, leaving standards like “Milk Cow Blues,” “Diving Duck Blues,” and “Drop Down Mama.” Across a career that stretched from 1929 field sessions to international tours in the 1960s–70s, he helped re-center rural acoustic blues in the American canon.

Childhood

Estes was born in Ripley, Tennessee—sources differ on the exact year (often given as 1899, 1900, or 1904)—to a large sharecropping family. He learned guitar from his father, Daniel, around age twelve and even fashioned cigar-box instruments as a child. A childhood accident left him blind in one eye. The nickname “Sleepy” has been attributed to his drowsy appearance and bouts of dozing, sometimes linked to a health condition.

In about 1915 the family moved to Brownsville, which would remain Estes’s lifelong home base and the setting for many of his character-rich songs. There he came under the sway of local musicians like “Hambone” Willie Newbern and forged early bonds with harmonica player Hammie Nixon and mandolinist Yank Rachell.

Youth

By his late teens, Estes was playing at house parties and fish fries around Brownsville. In the late 1920s he and Nixon gravitated to Memphis, joining Rachell and jug player/pianist Jab Jones as the Three J’s, a jug-band outfit that worked Beale Street and competed with the Memphis Jug Band and Cannon’s Jug Stompers. The Victor field unit that came to Memphis in September 1929 captured Estes’s first sides, launching a recording career that would soon yield enduring titles.

Adulthood

Through the 1930s Estes split time between Memphis and Chicago, recording for Victor/Bluebird and Decca while playing house parties, lumber camps, and street corners. His records—often pairing guitar and that “crying” voice with Rachell’s mandolin, Jones’s piano, and Nixon’s harp—stood out for vivid, local storytelling (“Working Man Blues,” “Lawyer Clark Blues,” “Floating Bridge”). By the early 1940s he had returned to Brownsville; his eyesight failed completely later in the decade, and post-war sessions were sporadic and commercially modest.

In 1962 filmmaker David Blumenthal found Estes living in a sharecropper’s shack near Brownsville and alerted Delmark’s Bob Koester. New Chicago sessions produced The Legend of Sleepy John Estes and a run of albums that restored his profile. Festivals (including Newport, 1964) and tours of Europe followed, where audiences greeted him as a master of acoustic blues. He frequently performed with his old partners Nixon and Rachell during this renaissance.

Major Compositions

Estes’s catalog blends personal memoir with social observation, often naming townspeople and local institutions. Among the most influential and frequently cited are:

- “Milk Cow Blues” (1930): An uptempo Victor side whose melody and theme echoed widely—Robert Johnson’s “Milkcow Calf Blues” is a closely related variant.

- “Diving Duck Blues” (1929): A signature pre-war number, revived during the 1960s; included on Smithsonian’s 1929-1940 anthology.

- “Someday Baby / New Someday Baby”: Later known in other artists’ versions as “Worried Life Blues” or “Trouble No More.”

- “Drop Down Mama” (1935): A Chicago-era staple pairing plaintive voice and harmonica.

- “Brownsville Blues,” “Working Man Blues,” “Lawyer Clark Blues,” and “Floating Bridge”: Songs that memorialize people and places from his hometown and the trials of laboring life.

Critics and peers consistently praised his “crying the blues” style—Big Bill Broonzy’s phrase—while the Blues Foundation later emphasized the poetry and everyday insight of his lyric voice.

Death

As he prepared for another European tour, Estes suffered a fatal stroke at his Brownsville home on June 5, 1977. He is buried at Durhamville Cemetery in Lauderdale County. His small Brownsville house, moved to the West Tennessee Delta Heritage Center campus, is preserved as a public exhibit.

Conclusion

Sleepy John Estes stands as a quintessential voice of country blues: an artist who distilled the cadence and characters of West Tennessee into songs that traveled the world. From jug-band corners and Depression-era parlors to 1960s festival stages, he sustained a distinctive narrative blues—intimate yet archetypal—that continues to shape the idiom. Posthumous recognition, including induction into the Blues Hall of Fame in 1991, underscores a legacy built on specificity of place, generosity of feeling, and a truly singular sound.

Comments are closed