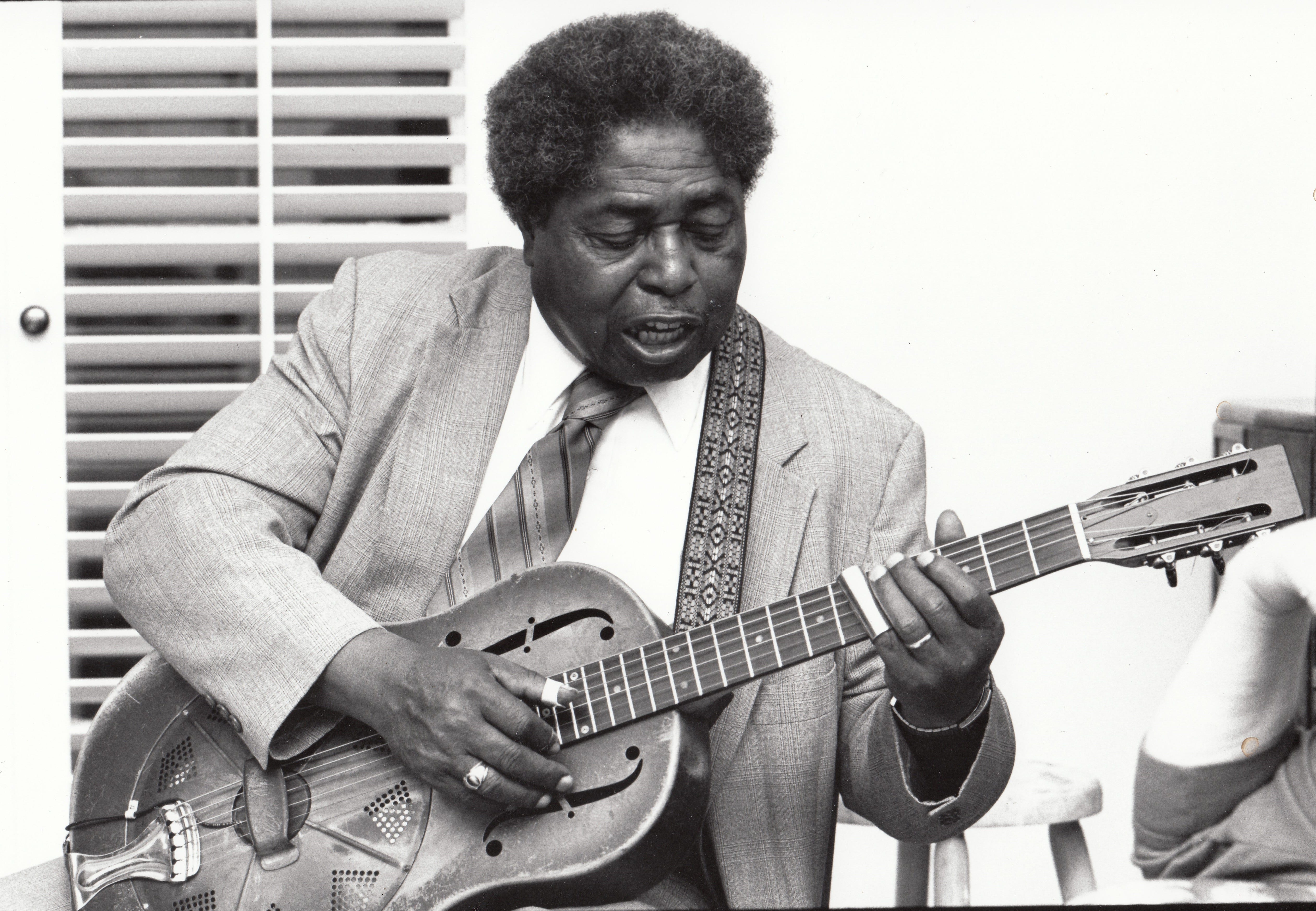

Johnny Shines – A Complete Biography

Introduction

Johnny Shines (born John Ned Shines, April 26, 1915 – April 20, 1992) was a towering voice of Delta and Chicago blues whose career traced the music’s great migration—from Southern street corners and juke joints to postwar Chicago’s electric scene and, later, the folk-blues revival circuit. A gifted slide guitarist with a full, ringing tone and a commanding tenor, he was both a vital link to earlier masters and an independent stylist, equally respected for his original songs and his definitive interpretations of classics associated with his friend and traveling partner, Robert Johnson. Shines’s story is as much about endurance as it is about artistry: false starts at record labels in the 1940s and 1950s, years of hard labor offstage, a late-life rediscovery, and, in the end, recognition as one of the music’s essential voices.

Childhood

Shines was born in Frayser, Tennessee, a farming community that later became part of Memphis. His mother played guitar and taught him his first chords, and the boy absorbed the sound world around him—church hymns, street vendors’ cries, and the raw, propulsive rhythms coming from neighborhood house parties. By his early teens, he was playing slide on street corners and in local “jukes,” sharpening a style that mixed strict time with vocal-like bends and percussive attack. Those formative Memphis years placed him close to major currents of Black migration and culture, and they gave him a deep, practical understanding of how to command a crowd with only voice and guitar.

Youth

In the early 1930s, Shines moved to Arkansas to work farm jobs, briefly stepping away from music. A chance meeting with Robert Johnson in the mid-1930s changed everything. The two traveled widely—throughout the South and as far as Canada—busking, playing dances, and “cutting heads” on street corners in friendly rivalry. The partnership was crucial: it honed Shines’s already formidable technique and broadened his repertoire, and it later made him an authoritative standard-bearer for Johnson’s songs. But Shines was never a mere imitator; even in this period his own writing and phrasing marked him as his own kind of blues poet.

Adulthood

Shines settled in Chicago around 1941, joining the wave of Southern musicians transforming the city’s clubs and studios. Early recording attempts—sides cut for Columbia in 1946 and for Chess in 1950—were shelved, a dispiriting setback that pushed him back toward construction work to support his family. In 1952 he recorded fierce, country-inflected electric blues for the small J.O.B. label; though the records didn’t sell, they later came to be prized for their knife-edge intensity and superb guitar work.

Like many of his generation, Shines’s public profile dimmed in the late 1950s and early 1960s—until the folk-blues revival found him again. In 1966 he contributed searing performances to Vanguard’s influential anthology Chicago/The Blues/Today!, which introduced a new, largely white audience to veteran artists. Tours and festival dates followed. In 1969 he moved to Holt, Alabama, near Tuscaloosa, making the small community his base while he worked the international circuit. The 1970s brought steady activity onstage and on record, including collaborations with Robert Lockwood Jr., Johnson’s stepson and another master of intricate, pre-war-rooted guitar styles. Even after a stroke in 1980 limited his guitar playing, Shines remained a powerful singer and a magnetic presence, sustaining a late-career run that culminated in awards and an affectionate documentary appearance.

Major Compositions (Recordings & Signature Works)

Although blues artists often interpret and reshape shared repertoire, Shines left a personal stamp on many titles and produced notable originals. Highlights include:

- “Standing at the Crossroads.” A defining performance that crystallizes his link to Johnson while showcasing Shines’s own authority—urgent vocals over ringing slide figures, equal parts lament and proclamation.

- J.O.B. Sessions (1952). Gritty, close-miked sides that capture his postwar Chicago power: taut grooves, razor slide, and lyrics that balance boasting with vulnerability. These recordings later became touchstones for collectors and musicians studying the handoff from acoustic Delta styles to small-band urban blues.

- “Last Night’s Dream” (1968, album). A late-’60s high point, widely praised for its spacious sound and intimate focus on voice and guitar, with Shines’s narratives of love, betrayal, and hard traveling delivered in a resonant, unhurried cadence.

- “Too Wet to Plow” (1977, album). A mature, roots-true set that shows the ease and depth of his phrasing in middle age—laconic, wise, and unsentimental.

- “Back to the Country” (1991, album, with Snooky Pryor and Johnny Nicholas). A late-career triumph that earned major honors and underlined what fans already knew: even after health setbacks, Shines could summon the old fire—ornate slide filigree when he played, gospel-tinged vocal power always, and a storyteller’s timing.

Beyond these touchstones, Shines remained a first-rank interpreter of “Kind Hearted Woman,” “Sweet Home Chicago,” “Sittin’ On Top of the World,” and other standards, bending them to his voice without sacrificing their lineage. His songwriting, meanwhile, tended to plainspoken images—roads, weather, quarrels, fragile truces—delivered with a preacher’s timing and a street singer’s bite.

Death

In early 1992, worsening circulatory disease led to hospitalization in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and the amputation of his left leg. Johnny Shines died there on April 20, 1992, a few days short of his 77th birthday. He was mourned across the blues world as one of the last, and best, of the Delta tradition’s bearers, a singer-guitarist who bridged eras without nostalgia or gimmickry—simply by telling the truth in time and tune.

Conclusion

Johnny Shines embodied the arc of 20th-century blues: a Southern childhood steeped in church and juke; road-hardened youth beside a legendary peer; postwar dreams in Chicago’s clubs and studios; long spells of work and waiting; and, finally, renewed acclaim among new listeners who heard in him the undimmed power of the idiom. If his life illustrates the music’s precarious economics, his art shows its permanence. The guitar glints and moans; the voice carries pride, hurt, humor, and defiance. And in the space between the two, Shines left a legacy that still teaches—about touch and tone, about phrasing and feeling, and about the stubborn beauty of the blues.

Comments are closed