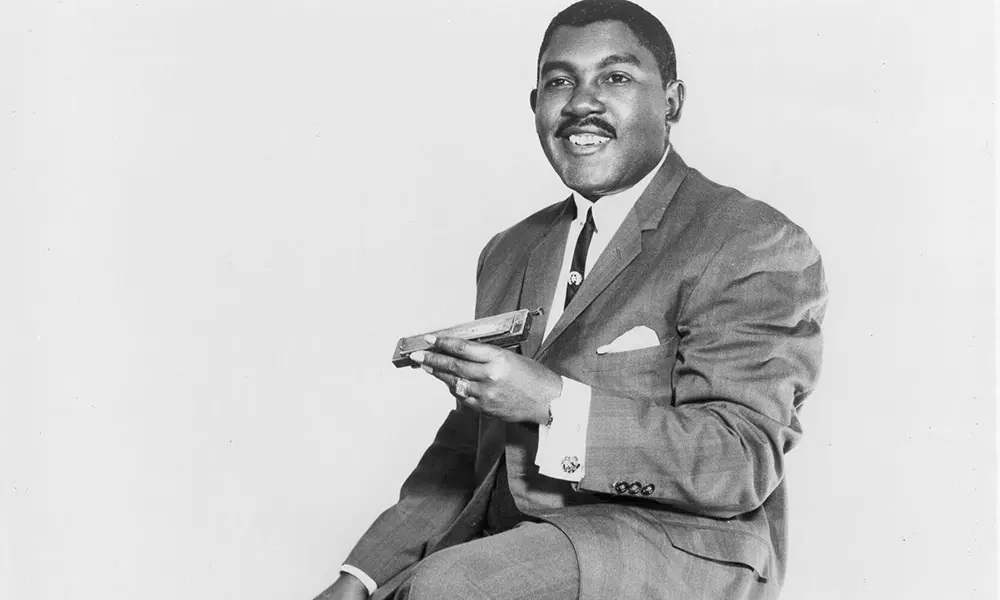

Junior Parker – A Complete Biography

Introduction

Herman “Junior” Parker—often billed as Little Junior Parker—was one of the velvet-voiced architects of postwar Memphis blues. A gifted singer and harmonica player with an easy, honeyed tone, he bridged down-home blues and the urbane polish that would feed soul, early rock ’n’ roll, and R&B. In a career that spanned just two decades, Parker cut enduring sides for Sun and Duke, toured relentlessly with top-flight bands, and left a songbook that still ripples through American music—most famously “Mystery Train,” later propelled to wider fame by Elvis Presley. His story runs from Delta fields near Bobo, Mississippi, to Beale Street bandstands, to national charts—and ends too early, at 39.

Childhood

Parker’s early years unfolded in the Mississippi Delta, a region where radio signals and Saturday dances braided church harmony with jukes and raw country blues. Family moves took him to West Memphis, Arkansas, while he was still young, and he soaked up the sound of Rice “Sonny Boy Williamson II” Miller’s King Biscuit Time broadcasts out of Helena. By the time most kids were worrying about schoolyard games, Parker had a harmonica in hand and a repertoire shaped by gospel quartets and local bluesmen. Those experiences gave him two signatures he never lost: a warm, unhurried phrasing as a singer and a succinct, conversational approach to harp.

Youth

In his teens and very early twenties, Parker learned on the job alongside giants. He gigged under the tutelage of Sonny Boy Williamson II and spent time around Howlin’ Wolf’s outfit, absorbing lessons in bandleading and stagecraft. In Memphis, he fell in with the loose fraternity later called the Beale Streeters—future stars like B.B. King and Bobby “Blue” Bland—where musicians traded songs, sideman shifts, and hard-won tricks of the road. By 1951 he had formed his own band, the Blue Flames, featuring razor-edged guitarist Pat Hare, and was drawing attention beyond the local circuit.

Adulthood

The first major break came in 1952, when Ike Turner—moonlighting as a talent scout—spotted Parker and cut his debut for Modern Records. The following year Sam Phillips signed him to Sun, where Parker and the Blue Flames recorded “Feelin’ Good,” “Love My Baby,” and “Mystery Train.” Those Sun sides, raw but tightly arranged, captured Parker’s strengths: supple vocals up front; terse, ringing guitar figures; and arrangements that left air for the groove.

By 1954 Parker moved to Don Robey’s Duke label in Houston, a long, fruitful association that sharpened his sound and broadened his reach. Backed by bandleader Bill Harvey and a revolving cast of first-rate players, he notched national R&B hits—most notably 1957’s “Next Time You See Me,” which also crossed to the pop charts. Touring grew more ambitious; Parker shared bills and bandstands with Bobby “Blue” Bland and others on the chitlin’ circuit, presenting a sophisticated, suit-and-tie blues revue that felt as polished as it was passionate.

The 1960s brought stylistic evolution. Parker never abandoned blues, but he folded in the sleek contours of soul, experimenting with fuller horn charts and contemporary repertoire. He recorded for Mercury, Blue Rock, Minit, Capitol, and others after leaving Duke, issuing albums like Driving Wheel and Like It Is (Baby Please). He even cut inventive covers—Beatles tunes among them—and teamed with jazz organ great Jimmy McGriff, proof of a restless musical curiosity. Through it all, his voice remained unmistakable: warm, rounded, and deeply human.

Major Compositions

“Mystery Train” (1953). Parker’s most famous composition, built on the propulsive image of a train that “took my baby,” is a masterpiece of economy—laconic vocal lines, loping rhythm, and a guitar figure that coils like steam. Elvis Presley’s 1955 cover made it a rockabilly standard, but Parker’s original carries a darker, bluesier undertow.

“Feelin’ Good” (1953). A breakout R&B hit, “Feelin’ Good” announced Parker as a national presence. It showcases his elastic timing and a band sound that feels both tough and urbane, with stinging guitar and buoyant shuffle.

“Love My Baby” (1953). The flip of “Mystery Train” features Pat Hare’s biting guitar riff—an influence heard in later rock ’n’ roll phrasing—and Parker’s relaxed but persuasive croon.

“Next Time You See Me” (1957). Perhaps his most broadly known Duke single, it pairs a suave vocal with a buoyant horn arrangement and an instantly memorable chorus. It became a staple for later generations of blues and soul performers.

“Driving Wheel” (1961/62). A signature album cut and stage favorite whose lyric of motion and weariness fits Parker’s train-track mythology. The tune’s rolling pulse and conversational delivery show how he could modernize the blues without losing its emotional center.

Other standouts. “Mother-in-Law Blues,” “Barefoot Rock,” and later, the adventurous soul-blues of the late 1960s sessions, round out a catalog that is both cohesive and surprisingly varied.

Death

In the autumn of 1971, still active in the studio and on the road, Parker underwent surgery for a brain tumor in Blue Island, Illinois, and died on November 18 at the age of 39. Posthumous releases gathered recent sessions and live collaborations, underlining how much music he still held in reserve. In 2001, recognition arrived in the form of induction into the Blues Hall of Fame—long after fellow artists and fans had already placed him there in spirit.

Conclusion

Junior Parker’s legacy rests on a rare blend of craft and feeling. He could sell a lyric with the ease of a pop crooner yet keep a bluesman’s conversational intimacy; he fronted bands that were tight, urbane, and dance-ready while never losing the Delta’s shadow. His compositions helped shape early rock ’n’ roll and modern R&B, and his recordings for Sun and Duke remain touchstones for singers who prize warmth over pyrotechnics. Had he lived longer, Parker might have ridden the 1970s soul-blues wave into new mainstream territory. Even so, the records he left—compact, elegant, and deeply musical—tell the story of a singular voice that still carries.

Comments are closed