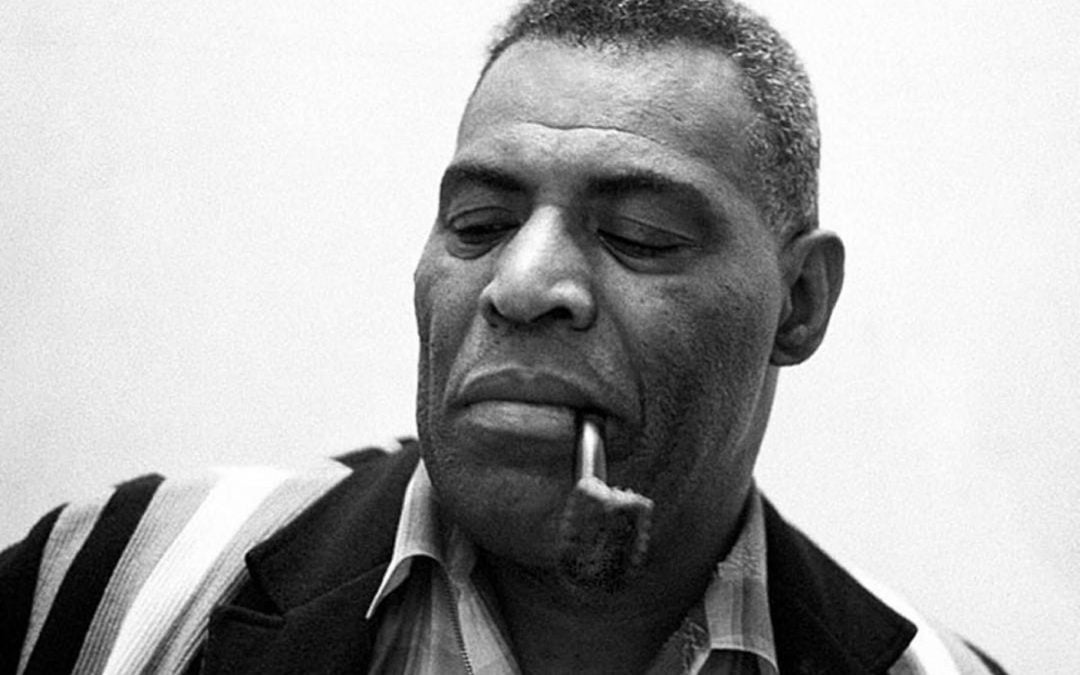

Howlin’ Wolf – A Complete Biography

Introduction

Howlin’ Wolf—born Chester Arthur Burnett—was one of the towering architects of post-war electric blues. With an immense, grainy baritone, a physically commanding stage presence, and a catalogue of definitive sides for Chess Records, he helped transform rural Delta idioms into the amplified Chicago sound that would shape rock and soul worldwide. His recordings such as “Smokestack Lightning,” “Spoonful,” and “Killing Floor” became standards, inspiring artists from the Rolling Stones to Jimi Hendrix.

Childhood

Burnett was born on June 10, 1910, in White Station, near West Point, Mississippi, to Leon “Dock” Burnett and Gertrude Jones. Family turmoil marked his early years; after his parents separated, he lived for a time with a harsh great-uncle before running away as a teenager to rejoin his father in the Delta. The nickname “Wolf” came from stories told by his grandfather to scare the boy—an epithet that stuck and later became his stage name.

Youth

In the Delta, Burnett encountered the legendary Charley Patton, who showed him guitar chords and a showman’s swagger; he later picked up harmonica ideas from Sonny Boy Williamson II (Rice Miller). Throughout the 1930s he farmed and performed around Mississippi and Arkansas. He enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1941 and received an honorable discharge in 1943, then returned to farming and weekend gigs.

Adulthood

By 1948, Wolf had moved to West Memphis, where he led a hard-hitting electric band and hosted a daily slot on KWEM radio that sold farm goods between songs. Producer Sam Phillips recorded him in 1951; those sides (“Moanin’ at Midnight” / “How Many More Years”) were leased to Chess and became a double-sided hit. Chess soon brought him to Chicago in the early 1950s. There he cut a long run of classics with bandmates including guitarist Hubert Sumlin and songwriter-bassist/producer Willie Dixon, and he emerged—alongside Muddy Waters—as a pillar of the city’s blues scene.

Wolf’s LPs helped codify modern blues: Moanin’ in the Moonlight (1959), a compilation of his 1951–59 singles, and the self-titled 1962 set often called The Rocking Chair Album. He toured widely through the 1960s, appeared on Shindig! at the request of the Rolling Stones, and cut The London Howlin’ Wolf Sessions (1971) with admirers Eric Clapton, Charlie Watts, Bill Wyman, Steve Winwood, and others.

Major compositions (and signature recordings)

Although Wolf both wrote and interpreted material, many of his signature Chess records—“Spoonful,” “Back Door Man,” and “Little Red Rooster”—came from Willie Dixon’s pen, while Wolf’s own writing yielded evergreens like “Smokestack Lightning” and “Killing Floor.” Moanin’ in the Moonlight gathered “Smokestack Lightning,” and the later Howlin’ Wolf (1962) bundled a run of Dixon-fueled hits that defined his mature sound. In Britain, “Little Red Rooster” reached No. 1 via the Rolling Stones, amplifying Wolf’s international impact.

- “Smokestack Lightning” (1956) — a hypnotic one-chord vamp Wolf had been shaping since the early 1930s. It reached No. 11 on the R&B chart and later entered the Grammy Hall of Fame.

- “Killing Floor” (1964) — a defining Chicago-blues riff that became a staple for rock bands, with Led Zeppelin reworking it as “The Lemon Song.”

Death

Years of grueling travel and health problems—heart trouble and kidney failure—caught up with Wolf in the 1970s. Diagnosed with a brain tumor in early January 1976, he underwent surgery at the Hines V.A. Hospital outside Chicago and never recovered, dying on January 10, 1976. He is buried at Oak Ridge Cemetery.

Conclusion

Howlin’ Wolf’s legacy is as vast as his voice. A primal vocalist with impeccable command of band dynamics, he bridged the field holler and the amplifier, turning the blues into something both theatrical and deeply modern. Posthumous honors reflect that reach: induction into the Blues Hall of Fame in 1980 and the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1991, as well as permanent enshrinement in the standard repertoires of rock and blues musicians worldwide. His records still sound freshly dangerous—and foundational.

Comments are closed